“So Matilda’s strong young mind continued to grow, nurtured by the voices of all those authors who had sent their books out into the world like ships on the sea. These books gave Matilda a hopeful and comforting message: You are not alone.”

Matilda by Roald Dahl

I stand on the scale, step off, heave a suitcase into my arms, and weigh myself again. The difference is 53 pounds, three over the limit. Sighing, I push my sweaty bangs out of my eyes, and reprioritize the piles of writing guides, and used, yellowed paperbacks, and novels with the jackets still crisp and clinging. I consider the weight of a Pulitzer prize winning hardcover and compare its hours of pleasure with a handful of my small daughter’s clothes, which may not even fit by the sixth chapter. I hold up Slouching Toward Bethlehem in one hand and a twin pack of Emetrol in the other, wondering which one I’ll appreciate more when I’m puking.

For nearly a decade I have lived in sub-Saharan Africa in countries where book shops and libraries are rare. Returning from yearly visits to the US, I devote at least 50 pounds of my luggage allowance to books, and greedy for the comfort of stories, the stimulation of quirky nonfiction, the methodical lyricism of essay anthologies, it’s never enough. I sneak more on the plane stuffed in the pouch of my daughter’s stroller, or in a plastic shopping bag, freshly purchased from Hudson News at gate A1.

Like Roald Dahl’s heroine Matilda, I find reading is the antidote to loneliness, the plague of expats who by nature of having many homes, often feel like they have none. As I stuff the new Louise Erdrich in my bag, Bird by Bird, and a stack of Rachel Isadora fairy tales, the number on the scale climbs.

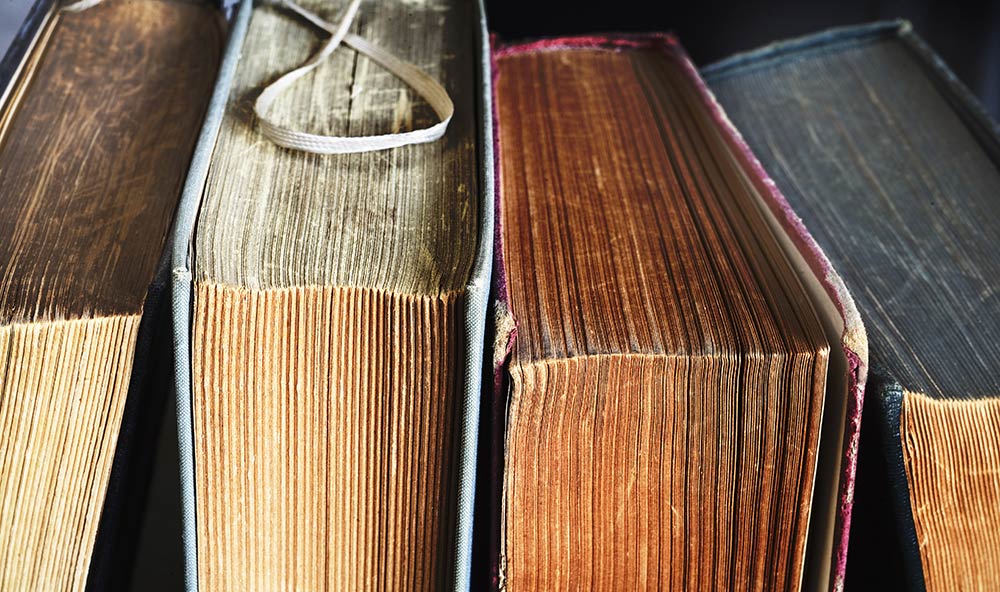

An e-reader would circumvent the weight restrictions, but I crave the sensorial experience of physical books: the heft, the crackle of pages, the smell of must and binding glue. I can’t press an e-book into a someone’s hands as a foray into new friendship. And “real” books make any new space instantly mine, the spines lined along my shelves spelling out, in addition to their titles and authors, h-o-m-e.

I grew up with a large public library, a small independent bookstore, and a huge Barnes and Noble all at my sticky, page-turning fingertips. Then I attended college a few steps from The Strand’s famous 18 miles. The availability of books in my subsequent homes has not been the same. But just as we carve watermelons into jack-o-lanterns at Halloween and schedule laundry day around power outages, expatriate readers adapt.

Moving sales, book swaps, international school libraries, hotel gift shops, trips to book stores in lieu of actual sightseeing on vacation, and begging diplomatic pouch privileges from my American embassy friends have built reassuring piles of reading material on the window ledge beside my bed. A surf shop on the coast of Mozambique rents books for $20, and gives back $16 upon their return. $4 was a small price to pay for hours sunk deep into Bee Season parked in front of the crashing Indian Ocean, when living out of a backpack for three months left space for little other literature than a Lonely Planet guide. In the capital city of Addis Ababa, a man known as Mr. Magazine tugs around a briefcase stuffed with issues of The Economist, hot off the press and considerably cheaper than newsstand price. From these sources, I gather stories, swallow them whole, and briefly forget I am far from a home I can’t name.

Reading drives cracks through foreign places, letting light in to render them a little less opaque. As a university student studying in Ghana, I sank my teeth into Ayi Kwei Armah and Ama Ata Aidoo, small puzzle pieces of understanding during my first experience outside of the US. As I moved across the continent, I read Murder at Morija in Lesotho, A Bend in the River in Congo, and The Beautiful Things That Heaven Bears in Ethiopia. In the latter, a novel by Dinaw Mengestu, the character Sepha keeps for many years a pair of old cuff links, his only memento of his late father and ponders, “I don’t think he ever intended them to become heirlooms. They were just cheap cuff links…but you hold on to what you can and hope the meaning comes later.”

Readers intimately understand holding on to things. For eight years, I hauled a Vikram Seth biography between four homes in as many countries before finally cracking it open. Two Lives is the story of Seth’s aunt, Henny and uncle, Shanti, and their decades long marriage across religious and racial barriers, a relationship that first began when Henny’s Jewish family took Shanti in as a lodger in Berlin just prior to WWII.

Two Lives is a love story, but it is also a story about home, belonging, and the clash and merge of cultures. For years I carried around these words before finally reading them: “Shaken about the globe, we live out our fractured lives. Enticed or fleeing, we re-form ourselves, taking on partially the coloration of our new backgrounds. Even our tongues are alienated and rejoined – a multiplicity that creates richness and confusion.” These lines held a mirror to my own face. My life of constant moving is fractured to be sure, the rootlessness often lonesome, but somehow reading the words about a married couple long dead while feeling as though they were also about me, scraped some of the loneliness away.

My copy is a paperback, but a hefty one, just half an ounce shy of a pound. I could KonMari it and rip out page 403, reducing the mass to a tenth of an ounce. I could type the words in an email to myself, rendering them weightless even while realizing the words are not weightless at all, but dense with meaning and heavy with recognition. Or I could drag them around, still bound, for a little while longer, illuminating them by lamplight and head torch and generator powered bulb, and one day just maybe press the dog eared pages into someone else’s hands.

Sara Ackerman is a writer and kindergarten teacher. Her writing appears or is forthcoming in The New York Times, Brain, Child Magazine, Creative Nonfiction’s anthology What I Didn’t Know and others.

2 Questions with Sara Ackerman:

TD: Tell us a little about this story? Where did the idea come from?

SA: I wrote most of this essay when I was in Kenya and even though I was only there for a week I was trying to pack this fat stack of books in my suitcase. And a few months before that I had been lugging some of these same books on multiple flights from the US to Ethiopia where I live. I started thinking about why I drag books around in the impractical way that I do when technology has found a sort of solution to that. People tell me to get an e-reader, but there is something compelling about carrying these physical objects with me and holding on to them across years and places.

TD: Do you handwrite your work or go directly to the keyboard?

SA: If I have my computer with me, that’s where I’ll start. I type fast so I can almost keep up with my thoughts at the computer. I hate reading on a screen though, so I have to print my writing to look at it. Then I handwrite all the edits and go back to the computer to type them in. This repeats until some murky-feeling point of completion.

lords mobile hack online

15 April

I needed to thank you for this amazing read!! I definitely appreciating every

little touch of it I have you bookmarked to check out

new material you post.

Maxine

19 April

Greetings! Very helpful advice on this post! It really is the small changes that make the biggest changes.

Thanks a lot for sharing!

respawnables hack ios 2017

20 April

Saved as a favorite, I really like your site!

Walker

23 April

You should participate in a competition for one of the finest

websites on the internet. I ‘m going to recommend this site!