My partner Roger earned two free tickets on an American airline anywhere to Europe several years back and asked me where I wanted to go.

We considered Italy or Greece – a warm destination was preferable – maybe a little out of the way place in Sicily, we’d never been. Southern Italy, however, would be expensive. The carrier only flew to Milan, and we’d have to pay for connecting flights on our own. I mentioned taking the train to Naples – “If it’s over five hours, I think I’d prefer to fly,” he said – and renting a car. “Automatics are very expensive in Europe,” he said. “You really want to drive?” I was stuck. As a writer and part-time billing clerk, I make little money and so I usually leave travel arrangements to him. “I’ll go wherever you want,” I said. “No, this is your trip,” he said suddenly, “I want to make you happy.” It went on like this for a few weeks. “I’ll pay for the interconnecting flights if we need to,” he said. It didn’t really matter to me, either. I’ve seen a lot of the world and I am happy to be home. On a whim, however, I asked him how much it would be to fly to Egypt. Maybe if the carrier flew to Athens or Istanbul… I was intrigued, particularly, by Alexandria. I had thought about it several times before in our travel discussions, but Roger had already been to Egypt twice and I wasn’t sure if he would be interested in returning.

Nearly twenty years before, a friend of mine had introduced me to the poetry of Cavafy. I read everything that I could of his, several translations, one biography in English at the time, and I don’t think there was a reference to a Ptolemy or a Comnenus that I didn’t look up. I was living on Beacon Street in Boston and every time I had chores to run downtown it seems I’d drop in at the library and make my way inevitably to where they kept his books. I’d read for a few minutes Ithaca or a few lines from “In the Evening”.

In relationships that never lasted more than three months, I had my share of obsessions and encounters along the Esplanade and I think I was fertile ground for the obscure, illicit tendernesses I found in his poetry. I don’t think, however, I ever really entertained the idea of visiting Alexandria. I don’t think it ever seemed quite real to me: a city of memories and deadening melancholy and regrets.

Roger called me up several times a day from work to tell me that it was possible; we’d overnight in London and pick up our tickets from an agency that sold reduced fares to Egypt. He seemed excited, he always is when he’s planning on a new trip, but I told him, since we only had a few days, I would like to spend most of it in Alexandria. He didn’t mind. He hadn’t been to Alexandria, either. Months before, I chanced upon a copy of E.M. Forster’s Alexandria; A History and a Guide. On page 259, there was a fairly good map of central Alexandria, including, to my surprise, “Cavafy’s flat”. We made plans to stay at the Cecil Hotel which was within walking distance to most of the sights I wanted to see.

Surprisingly, the train to Alexandria didn’t make any stops to pick up passengers. We saw grass-green farmland, neat and orderly, irrigated by a canal and – indirectly – the western, Rosetta branch of the Nile. Acres of cotton, farm vegetables, rice. A few stands of trees which might have been citrus. The whole area is very fertile: plenty of water and plenty of sun and plenty of backbreaking labor. As the ride is only two hours long, I suspected we were fast approaching Alexandria and I wasn’t surprised to see a long line of apartment buildings on the horizon. Roger opened his eyes. “I think we are almost there,” I said, and he nodded. I was excited, a little apprehensive as we approached the city of Cavafy’s poems.

The houses, however, were tall, modern, apartment buildings, several stories high. The train crawled along to a stop, and after a few minutes and some indecision, we all got off. There were no signs and no one had called out the name of the stop. There are two train stations, however, in Alexandria; one, the main station Mahattat Misr towards the center of town at Republic Square and almost in walking distance to our hotel, and the other at Sidi Gabr Station. – This was the latter.

We carried our bags outside, and considering for a moment attempting the trams – colorful blue and yellow streetcars – we hailed a taxi. I was surprised to discover how far away from the old center of town we were as our taxi approached the harbor and we got our first panoramic view of the city; a beautiful half moon of a beach and tall, white high rises behind, brilliant in the sun. “and the summer Mediterranean lies before me in all its magnetic blueness. Somewhere out there, beyond the mauve throbbing line of the horizon lies Africa, lies Alexandria, maintaining its tenuous grasp on one’s affections… “ so Durrell wrote of it. We traveled westward along the Corniche, getting my first glimpse of Fort Qayt Bey at its tip, site of the ancient lighthouse of Pharos, the second of the seven wonders of the ancient world here in Egypt. On the right, the rocky beaches of the Eastern Harbor in a long sweep, and on the left the crowded apartments and commercial establishments of modern Alexandria.

. . .

The following morning was dry and hot. The sun shone directly overhead as we walked east, past the trolley station and the cars (along whose tracks, just east of the city, E. M. Forster was to meet Mohammed el Adi, the tram conductor, with whom in his thirties he was to share a deep love and first sexual relationship), along wide, busy Sharia Iskandar el Akhbar. The Greek Consulate and a reconstruction of Cavafy’s apartment (so we read) were at No. 63. There were tall apartment buildings, darkened with soot, on either side, and restaurants and shops on the lower floors. The apartment buildings were nearly a block long, six or seven stories high, wider it seemed than they were tall, with balconies on the upper floors; once beautiful perhaps but now grimy, run-down, and in desperate need of sandblasting. Still, we commented on the beautiful architectural details: Italianate in style, cornices, balconies, elaborate framework around the windows. The Greek Consulate, by comparison, was low, two or three stories high, gleaming white, surrounded by a tall wrought iron fence. Soldiers in uniform were stationed out front.

There was a bit of discussion as we explained to them that we were looking for the Cavafy Museum. A man from within the gate at the front entrance pointed to a side entrance to which we headed. Downstairs, behind counters, several people were counting money. One man spoke good English, nodded, but told us that it was closed. He told us to wait, however, as he finished, and walked us back outside. He hollered to the guard on the front step to let us through. Roger started to say something about how I was a writer, we had come all that way… He led us inside to a thin, middle-aged woman with dark hair behind a desk. She shook her head as she explained to us that the museum was no longer there. She went on to say that Cavafy’s furniture had been returned to the apartment. I had wanted to see the apartment, anyway, and I was delighted. She explained that the Greek government had attempted to buy the building outright, but the landlord wouldn’t sell. They had managed to secure a nine year lease – after that, she shrugged her shoulders, who knew? Yes, we could visit, she said – it wasn’t far, and handed us a hand-drawn street map. She seemed interested suddenly in where we were from. “Are you Greek?” she asked.

We said no. We were from the States, but we were familiar with his work. She nodded. We thanked her and said goodbye.

We followed our way back along the street to the tram station. From a distance, we could see what looked like oriental carpets being hung out on upper balconies, some beautiful tile work decorated the walls. At the Hotel Metropole we turned south (and east) down Sharia Zaghloul several blocks to the next large intersection, Sharia Sultan Hussein. We turned right and eventually crossed over. We were looking for the old Greek Hospital where Cavafy died, now a modern theatre. I saw no sign of either except a tall, square building set back from the street. Completely surrounded by small shops out front, it looked all but closed. Its gates were open, however, and we walked through into a small yard. There was a small street behind it to which we crossed and turning right again we fell upon 10 Rue Lepsius, now 6 Sharia Sharm el-Sheikh, with the famous plaques out front. Though written in Greek and Arabic, I thought I could make out the Greek spelling of his name and pointed it out. There’s an old picture of the doorway in E. M. Forster’s guide and a translation, which I read out loud. Cavafy lived in this house the last twenty-five years of his life, till 1933.

The building itself stood four or five stories high, grey stucco, with large wooden doors out front. Just above the door was a small rectangular window and above that a narrow balcony.

“I’m sure this is it,” I said and asked Roger to take a picture. I mentioned to him how Cavafy had lived upstairs from a brothel, the street was familiarly known as Rue Clapsius, across the street from the hospital, and around the corner from the Greek Orthodox Church, St. Saba. As the front door was open, we walked in. The ground floor entrance hall was quite large, and a worn, stone staircase at the back led up to the second floor. There was nothing to remind us of him in the dank hall but his poetry.

“The surroundings of the house, centers, neighborhoods

Which I see and where I walk; for years and years.

. . .

You have become all feeling for me.”

“In the Same Space”

Voices of children could be heard from outside as we walked upstairs. On the right at the top, a small sign read: Cavafy Museum. I pressed the bell and after a few moments we heard footsteps approach. The door opened and a young Egyptian man smiled as he greeted us. He was in his early twenties, dark, thin, with a moustache, dressed in jeans and a blue striped shirt. We shook hands – he smiled again, “Welcome” and invited us to look around. The doorway led into a long hallway; across from it were two tall half-empty bookcases. The man explained to us that he was the live-in caretaker. The apartment was quite spacious – several rooms led off the hallway – and blessedly quiet I thought for a writer.

Our guide led us into the bedroom first, a good-sized room with tall ceilings. A brass bed, low and square, with a yellow cover over it, was tucked against the left-hand wall. Above the bed was a kind of small wooden altar; behind panels of glass were portraits, icons, of Greek saints. Though beautiful, I was somewhat surprised. Ironic I thought for Cavafy, this poet of hidden, gay loves. There were photographs of family members along the walls – every room seemed to have several – here reproduced: his mother, a short, stout woman in a hat, fashionably dressed, two brothers with the young poet –then just a boy – between.

Our guide opened the window shutters for us to see the small balcony outside, the same one, apparently, we had seen from down below.

From the balcony, one could see what the poet must have looked out upon: the narrow alley of Rue Lepsius, the blank wall of the Greek Hospital diagonally across from him, the rooftops of Alexandria. At noon that day, it was relatively quiet. The sun outside was like a white heat.

As we turned back, I noticed three very old jugs, amphorae, on the floor, of painted terra cotta, the colors faded and peeling. One was faintly yellow. Their bottoms came to a point and as they could not stand on their own, they were enclosed in small metal frames which held them up. I hadn’t seen anything like them before. I remembered, though, two yellow jars described in his exquisitely painful “Afternoon Sun”.

“Near the door over here was a sofa,

and in front of it a Turkish rug;

close by, the shelf with two yellow vases.

. . .

Beside the window was the bed

where we made love so many times.

The poor objects must still be somewhere around.”

In “Afternoon Sun”

Next to the yellow jugs was a small wooden stand, a foot high, like a magazine rack, beautifully carved. We had seen a larger model in one of the mosques we had visited in Cairo; we were told that they were used to support the Koran. I asked the guide here if that was what they were used for and he agreed. I suppose Cavafy might have used it for a dictionary or a large family album. It stood empty.

There was a small alcove, at the top of the hallway, next to the bedroom on the right. We spent a few minutes here looking down into a glass-topped table where some first issues and correspondences of the poet were displayed. Family photographs lined the walls. Roger pointed out a simple picture of the hospital bed where he died, all in white. I noticed a hat on top of a cabinet in the background; I thought it might have been his.

Our guide led us into a large room next to it, on the right corner of the hallway. Across the room and diagonal to the door was a large desk with high-backed chair. The desk I thought where he reshaped Ithaca, his histories. Our guide explained, however, that Cavafy didn’t write there. “Too noisy,” he said. Like the bedroom, it was in the front of the house; with one large window on the left and one on the side it would have been affected by street noise. Sensitive to noise myself, I nodded. There were more pictures of his family including a photograph of his father’s store. There was a small wooden table under the window on the right and on it a rather unusual sculpture of colored glass. I thought I remembered a poem of his, “Of Colored Glass,” where, at his coronation, the Byzantine emperor, John Cantacuzenus, and his wife, wore artificial gems.

Our guide led us from the study into the first of two smaller rooms behind the hallway. A large wooden table stood in the middle, and on it publications of the poet’s work. The room beside it had another large table and more of his work translated into foreign languages, very few were in English, and none for sale. There was a tall, open bookcase in the first room, I believe, and on it in English were copies of a publication dedicated to the opening of the museum. There were some recently published essays about the poet’s work, that I hadn’t read before. I asked our guide if they were for sale, but he shook his head. “Part of the museum,” he said. Disappointed, I put it back. Most of the publications were in Greek, a few in English, mostly all paperback: translations or work related to Alexandria or to the poet, including The Alexandria Quartet and E. M. Forster’s Alexandria: A History and a Guide. The first publication in French of Cavafy’s poetry in the literary journal Quarante-Quatre (44). A few in Arabic, Spanish. Along the walls in both rooms were pictures, drawings, and sketches of the poet – in one photo, Cavafy as a young man with a moustache – pictures of his literary friends. I pointed to one young couple whom I hadn’t seen before. “Tsirkas,” our guide explained.

At the back of the house was a small kitchen and on either side three small bathrooms, installed several years back when the apartment functioned as a small pension.

The apartment, I thought, was quite large, ample even, with high ceilings, sparingly furnished. Some of the pieces might have been lost. It was certainly quiet and cool, and I could think of several writers or artists, myself included, who would have moved in that afternoon.

Our guide explained he was living there while he was going to school. He was quite friendly, probably relieved to have some company.

He led us up the hallway to a small desk. “Where the poet wrote,” he said.

A small window overlooked more or less a dry well and the apartments up and down. Our caretaker said it would have been quiet here. It seemed appropriate somehow for a night’s work. I thought I had read something about a couch, however, when Forster visited him, one of the objects possibly that had been lost. I find in “He Came to Read” mention of a sofa, but the boy is only twenty-three.

On the desk were several publications for sale, only one in English which I bought, the one I had been looking at in the other room. I was disappointed that there weren’t more.

On the opposite side of the desk along the hallway was a lovely, dark, mashrabiyya screen, four feet tall or so, of delicate, intricate latticework, used I suppose as a room divider. The screen effectively closed off the desk. Across from it stood the tall wooden bookcases -with glass doors we had seen when we first came in. Most of the shelves were empty but on the top two shelves were twenty or so books, all in Greek, histories I thought he would have consulted for his poetry. As I was looking through the glass doors, our guide opened one for me and said I could look inside. As I took one out, I was confronted with the stale scent of old musty books. I leafed through a few pages – it was Greek prose -and I put it back.

Before we left, I wanted to see the bedroom once again. As I was looking around, our guide commented somewhat naively to Roger and me: “Single. Never married,” and smiled.

We both nodded. I wondered if the boy had read his work or understood it. I confess as I left the bedroom, I touched the bed briefly, never expecting to be here in his room. I looked back once again at those objects he loved and walked out. We shook hands with our guide, thanked him with a few American dollars, “Shukran,” and said goodbye.

An old mirror hung next to the door, smoky, tarnished, the reflection could not have been very good. I suddenly recalled that poem of his about an old mirror, on whose surface a young man’s image had once appeared. In Rae Dalven’s translation, entitled “The Mirror in the Hall”.

The door shut behind us. We walked downstairs. Roger seemed to have enjoyed the visit, too, confiding to me suddenly he had touched the bed, too. We both laughed thinking about our guide’s sweet naiveté: “Single. Never married.” Outside, I looked back up. There was the balcony, the shuttered windows as he wrote of them.

I remembered reading years before Cavafy’s poem “Expecting the Barbarians” thinking foolishly not so much of the barbarians invading Rome but of the Arabs bearing down on classical Alexandria. I couldn’t imagine anyone writing about Alexandria- Egypt for that matter- without commenting on the beauty and generous hospitality of its people.

That night after dinner, I wrote postcards for awhile on the floor outside the room where Josephine Baker stayed (there were no plaques to Forster or Durrell that I could see). By now the chambermaids and bellboys had gotten used to me sitting there; they smiled as I tried to look comfortable.

The following night we walked along the waterfront for a few minutes. Many of the restaurants along the Corniche had their doors open, but there were few customers. We walked around the block, crossed the tracks, and found ourselves in front of Diamantakis. It was busy; it had a Greek name – not the one that we were looking for – and not to be disappointed once again, Roger asked, for me, if they served grilled shrimp, which they did. There was a friendly crowd out front. A man on the right was kneading what looked like pizza dough, and a man on the left was preparing souvlaki sandwiches to go. People were waiting to pick up their orders.

We were shown to a small table upstairs overlooking the entrance. Our waiter spoke good English, told us to help ourselves to the salad bar, and took our orders. Roger ordered fish and chips and I the grilled shrimp. We helped ourselves to several salad items: dried olives, peppers, tahini sauce.

A few minutes later, our waiter delivered our orders. We talked and laughed about some of the people we’d met – Cavafy’s caretaker: “Single. Never married.”; the sun bear at the zoo that afternoon. I think we were both pleased with our trip. I squeezed his hand a couple of times. I ordered coffee, some flan for dessert.

Our waiter came over with our check. He told us that his big wish was to go to America someday, “New York.” He asked us how we liked Egypt. I told him that I had never felt so welcome anywhere or had met such friendly people. “You mean that?” he asked. I nodded. He smiled; he seemed pleased. He hooked his two thumbs together. “America. Egypt. They’d be great together,” he said. “The 51st state.” We laughed.

We paid our bill and left a healthy tip for our waiter – I hope when he gets to New York someday, somebody will make it as memorable for him as they have made it for us.

I thought it would be nice to go for a walk and I mentioned to Rog there was only one more thing I wanted to see. I didn’t quite know how to say it. He seemed curious, “What is it?”

“I read about a street where Cavafy kept a room,” I said. “I guess that’s where he met boys. It’s not far,” I said, “but it was far enough so he wouldn’t get caught.”

“It’s okay with me,” he said.

I explained to him that in the old days, neighborhoods were cut off from each other – and that it was to one of these outlying neighborhoods where Cavafy would have gone at night.

I explained that before the revolution, when the foreign community here was pretty well self-governing, prostitution was legal, considered outside Egyptian law. It was thought that some of the boys Cavafy picked up, he met and paid for at the small room nearby.

In his poem “Perilous Things” we find a few lines spoken by Myrtias, a Syrian student in Alexandria, in the reign of Augustus Constans, yielding his body to amorous desires. The same lines, I suspect, Cavafy might have written about his own youth.

We walked south from our hotel several blocks and then turned west onto busy Hurriya. It was getting dark, but at nine, nine-thirty, the city, the shops were alive with traffic, people out for a stroll. As we traveled west from downtown, the streets seemed to darken. There were fewer people about, and only once did I need to check the map. Sharia Orabi, the street to which we were headed, was the last of three streets that intersect diagonally at Hurriya; it was easy enough to find. It was quite wide, however – in Cavafy’s day it was called the Rue Attarine (site of a spice and perfume bazaar from which it took its name, Souk al Attarin) – though much of the street looked as if it needed to be repaved. It was dark, there were infrequent streetlights, and we made our way carefully from one side to the other. The entire street seemed sunk in gloom. We didn’t have a number of course where the original house might have been. Walking up from Hurriya, we could see that nearly an entire block had been torn down on the left, and one long apartment building had been put up. The new grey facade offered little to the imagination, and we crossed over; the only thing that lifted the gloom around us was the yellow headlights of passing cars, unmindful of the potholes, and lights, but poor, that managed to make their way through shuttered windows. The apartment buildings were huge, run-down, their front doors open so that one had a good view of an empty, darkened vestibule, not unlike Cavafy’s own at Rue Lepsius, and at the back a half-circular stone stairway leading upstairs. A house, a street worthy of an Edgar Allan Poe.

We walked back across the street, better to see them from a distance – the tenements were square, massive, several stories high, brooding in their shadows of Italianate designs: heavy cornices and pediments darkened from soot, small balconies and rails. I wasn’t prepared for this overwhelming sense of despair.

The illicit purposes, anyway, were a dim memory. Most of the windows were shuttered and dark. We walked up to the next block and worked our way down again. The few yards and alleys were littered with debris; there were no shops, and nothing seemed to alleviate that overwhelming sense of gloom, even abandonment. I think I felt grateful that I had someone by my side. As I looked up at the brightly lit windows, I thought of Cavafy’s remorse, his feeble repentances.

We made our way over the broken sidewalks. I felt sad and wistful, happy to share this poet’s life with my friend. I said my goodbyes, and we turned onto Hurriya.

In the several days we had been in Egypt, I suddenly realized I had not seen one poster anywhere about AIDS. I commented upon this to Rog. He hadn’t seen one either. I remembered that in Indonesia there were posters everywhere. I couldn’t read the writing, but AIDS was spelled out in English and the traditional sword, the kriss, thrust through it. I hadn’t seen anything like that here, even in Alexandria, Egypt’s vacation capital.

The next morning, however, our last, Roger had definitely come down with some intestinal bug. I was still spared, surprisingly. He seemed listless, I did most of the packing, and over a quick breakfast, he confessed he wouldn’t be able to eat a thing. We tried to figure out what he had eaten – that I hadn’t. I thought it might have been something from the open buffet the night before. He’s a good soldier, however, unlike myself; he never complains, he restricts his diet, and despite his 104 pounds soaking wet, he has a remarkable constitution. Rarely does he get sick.

He was well enough, however, to settle up at the front desk, they seemed to have forgiven us anyway for the room change, and we hailed a taxi to the train station. Pigeons were flying about, and once again a stiff breeze was coming in off the water. There was little traffic at that hour. I looked around once or twice in the direction of familiar sites – Cavafy’s flat, of course, which I couldn’t see – and in a few minutes we were at the train station. I suffered from a little bout of melancholy. I never got to see Lake Mareotis, the great marsh area south of the city, and that Durrell had described so beautifully, one of many inspired passages, in his Quartet; I never saw the shop, Tea Grammata, the street where Cavafy’s work was first published. I never saw the tombs at Kom el Shugafa, the Nouzha Gardens – they’re there for some other traveler to write.

Our attendant took us to our seat. Roger took the window; in case he fell asleep he didn’t wish to be woken up by people passing in the aisle. He put his head down against his chest. “You okay?” I asked and squeezed his knee. He nodded. I felt grateful for this friend who had brought me here and concern now that he was sick. The train was about to pull out; the attendant was seeing the last few people to their seats. The train gave a faint tug and started to move. I looked out the window at the passing crowds, the high girders of the station; beyond was the modern Egyptian city of three million people. I was reminded of the warmth, the goodwill of its people. After a few minutes, we pulled into the second and outlying station; businesspeople in suits and briefcases were boarding, going to work in Cairo. On the skyline, the white balconies of Alexandria’s new apartment buildings sparkled under the morning sun. The train gave a faint tug – people were passing back and forth along the platform hurriedly, calling out – we started to move. I bid her farewell,” the Alexandria”, that I, too, was losing, from “The God Forsakes Antony.”

Robert Cataldo is the author of four novels: All my life. Since I told you, Until Then, Nights at The Napoleon, and Autumn. His work has appeared in Bay Windows, Zonë, a feminist journal for women and men, and several issues of Backspace, among others. A short short of his was published by Alyson in the short story collection The Day We Met. Two poems of his were also selected for the Rhode Island Writers’ Circle Award anthology for 2003. His poem, “Ancient Find” was published in Gradiva, International Journal of Italian Poetry, 2014. He lives in Providence with his partner of forty years.

Five Questions with Robert Cataldo:

TD: Tell us a little about this story. Where did the idea come from?

RC: When we got back from Egypt, many years ago now, I realized I didn’t want to lose the memory of our trip: the perfume maker’s shop in the Cairo bazaar, the ruins of the Ancient Library of Alexandria, the gracious people that we had met, but above all the poignancy of actually visiting Cavafy’s flat. I hadn’t read any recent visits to this poet’s home, the city that he loved, and for gay writers like myself, I was hoping it would fill in a few gaps.

My boyfriend, furthermore, is an adventurous, highly knowledgeable travel agent, who loves to plan trips, and without his expertise and goodwill, it would have been difficult to get there on my own, God knows, and not nearly as fun.

TD: Who is your greatest writing influence?

RC: I have had several, but first among those would be Constantine Cavafy, the Greek gay poet, who lived in Alexandria, Egypt. (He died of larynx cancer in 1933.) I was introduced to his poetry some forty years ago now by a kind, well-read friend. Even at that initial reading, I was haunted by Cavafy’s singular, melancholy voice: elegies for dead (male) lovers, sad, inglorious incidents from Hellenistic history, even a few lessons for young poets starting out. Even by then, in 1975, 1976, the gay, circumscribed world he described hadn’t much changed: the illicit encounters, the longings and loneliness, the ardor, the beauty of young men. I was enthralled. There was a time, particularly in the mid-seventies, when relationships, poor health, and family rejection took their toll, and I took comfort in reading a few lines from “In the Evening” or “Candles”, any of the “Days…” poems to give me a little encouragement, companionship on my way to work. At sixty-eight now, with a loving boy in my life for forty years, (married for five), I don’t think Cavafy could have anticipated all the changes gay life has undergone, the human family, if grudgingly, imperfectly, has come to accept. But it was his deeply felt, profoundly melancholy voice which I understood.

In one of several crises in my young life, I also chanced upon an anthology of Chinese poetry from the T’ang Dynasty, 618-906 A.D., The Jade Mountain, translated by Witter Bynner. In it, I discovered a handful of poems by the Chinese poet-sage, Tu Fu, who lived in exile in Chengdu, Szechuan Province. So far removed from the Mediterranean, Panhellenic world in which I was so thoroughly immersed, I would be remiss not to mention two poems of his with much influence on my life: “A Song of a Painting To General Ts’ao” a short narrative about a great artist, whose work and life have fallen upon hard times, and “A Song of an Old Cypress”, a tree, ancient and inaccessible, its trunk like “green bronze”, standing unmoved below the farthest reaches of the heavens. Short of cutting it down, little can be made of it. I have had, in comparison, a short human span to contemplate his always sympathetic words. Though I am primarily a prose writer, I have had these two poets’ reflections to help guide me through so many years.

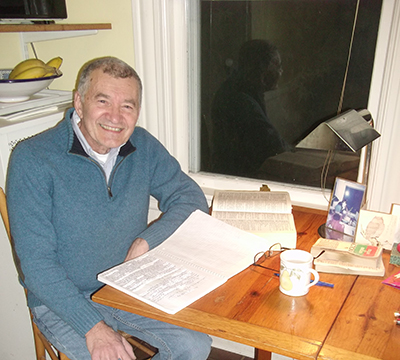

TD: What is your favorite place to write and why?

RC: I would say it would have to be the kitchen table. It’s quiet, it has a great view of the street, and it’s closest to the refrigerator and stove. If distracted or stuck, I can always find something to eat! I write in notebooks, primarily, and kitchen table surfaces are perfect for spreading out.

TD: Favorite word?

RC: I have two: “Trash”, a nickname that the boyfriend calls me when he’s feeling most affectionate; and murmuration, a fifty-dollar word for a priceless phenomenon, when starlings amass in huge flocks and fly about at close of day in great, seemingly, synchronized displays. I suppose the sound of 100,000 wings, at a great distance, is like a giant murmuring.

TD: Do you have a favorite reading ritual?

RC: My favorite ritual for reading would have to be, again, sitting at the kitchen table, late at night, with a cup of tea. Most likely I’ll be studying Italian, with several dictionaries open, or reading some obscure treatise on gay life. The boyfriend calls out from his room: a request for hot chocolate, some funny story about our dead cat, or travel incidents he never fails to repeat, some pretext even just to hear my voice. I love to do research when I’m reading, and flat kitchen surfaces are ideal for unfolding maps or propping up books. Otherwise, I squeeze in reading, a sentence or two, delivering body parts, in the hospital lab where I work!

COMMENTS ARE OFF THIS POST