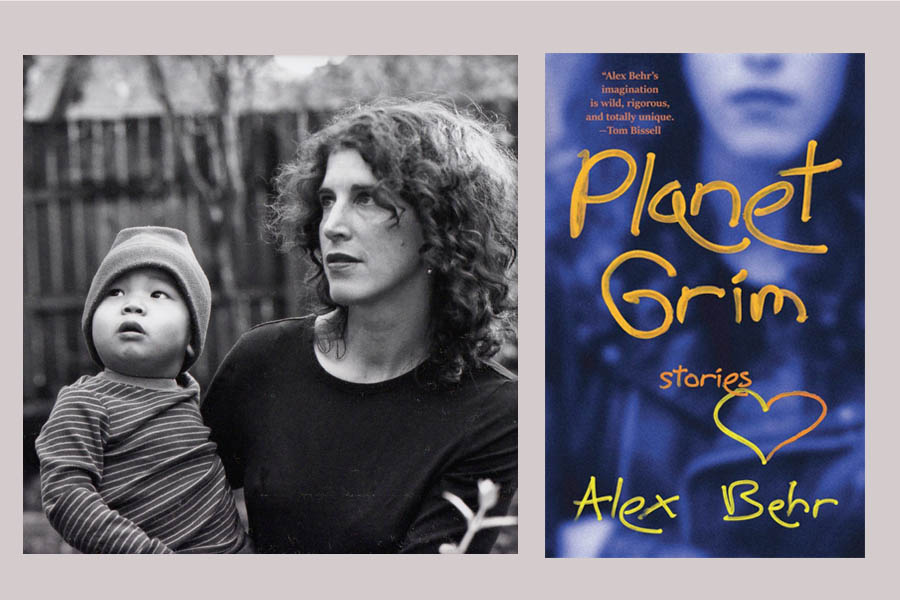

In Planet Grim (7.13 Books), the debut collection by Alex Behr, characters move through San Francisco, Portland—even Mars, looking for connection. Author Tom Bissell says, “Alex Behr’s imagination is wild, rigorous, and totally unique. I haven’t been able to decide if her stories are comedies intercut with horror or horror stories leavened by comedy, but when they’re this entertaining, who cares?” The book was included in The Rumpus’ list of “What to Read When You Need Some Good News” and Electric Lit’s “2017 Great Indie Press Preview.” Thoughtful Dog caught up with Alex about her process and the anxiety that comes with releasing a book out into the world.

TD: Are these stories that were written in a close time period or do these reflect your life at different stages?

AB: I wrote the first one around 2001 and the last one the winter of 2017, so they definitely cross my life at different stages. Some are products of workshops and grad school; others are fragments from notebooks. Some are diary excerpts, some of which were performed in the comedy show Mortified, some are found objects, and some are stories from overheard conversations. Some have not been edited, except very lightly by Leland (publisher).

TD: What was the process of working with Leland Cheuk of 7.13 Books to get this collection published?

AB: He asked me if I wanted to put a book out around the time my husband broke up with me (summer of 2015). I can’t remember the exact timing, but the two years of the long breakup (my husband still lived here for 18 months), divorce, subsequent move by my now ex-husband to China, and life as completely single parent of an adolescent (whom we adopted; he already has abandonment issues) corresponded with compiling the stories, rejecting some of the longer ones, editing, re-editing, begging Leland to add even more people to my acknowledgements page, redoing the cover with a last-minute blurb by Lidia Yuknavitch … Since it’s very DIY, I worked closely with Leland and the book designer (the wondrous Gigi Little), the eBook pro I hired (Cyrus Wraith Walker), the very patient, clever, affordable publicist (Lori Hettler), etc. He had a great marketing sheet he gave me that basically said: this is a hand-sold book. You do what you need to do to become comfortable with marketing it, but there is no sales force. No one is asking a bookstore to carry it besides me. I set up 10 readings, mostly on my own, and Leland was there to support all that, too. He basically should charge me for therapy. I owe him a lot! He’s been unusually patient. I’ve known him since the early 2000s. I’ve kept up with his writing over the years and read/commented on drafts for him—some of which have been published as books. He is fearless (standup comedian), politically astute, and very gifted.

TD: I love that you’ve said that putting yourself out there—whether it be in advanced copies—or having your friends read this is giving you some anxiety. While every writer dreams of being published, there is an intimacy that you have with your work that ends when you’re sending out reviewer copies. What has that been like?

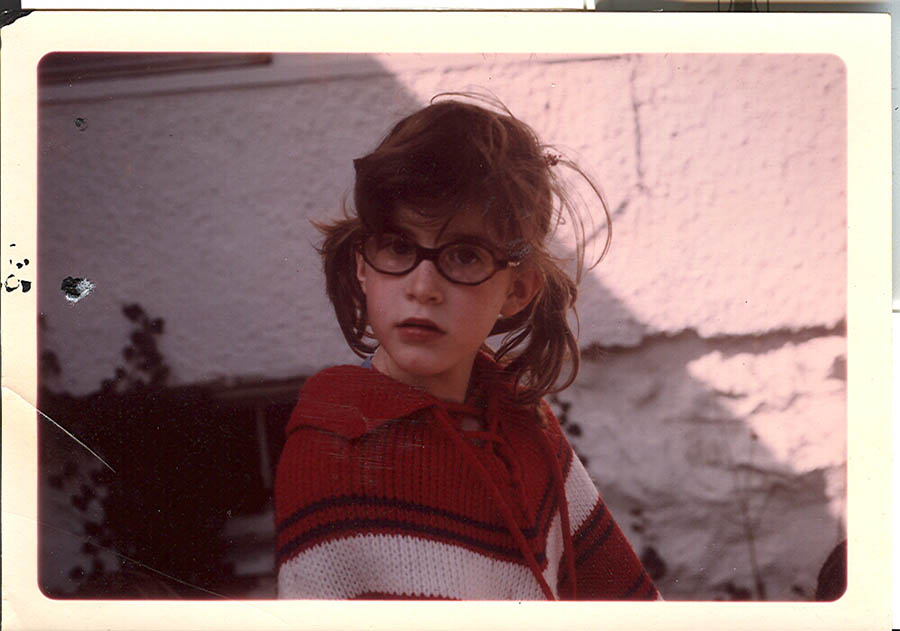

AB: It’s been hard. I’ve had a lot of anxiety and nightmares. I dream that the words melt on the page or the bottom of the page turns brown and disintegrates (the only good thing about that one was that I was in Austin with King Coffey from the Butthole Surfers and Craig Stewart, who put out one of my CDs by my former band). I have a discordant personality in that I want to please my parents, who would never read this content, yet I write what I write. Like in seventh grade (spring of 1978), I wrote about meeting a strange man outside a hardware store; I was waiting for my dad, and had our dog on a leash: “He got in a conversation with me about dogs. When he talked to our dog Casey he spoke in a really high voice. I thought he was strange then, but when he came back he started praying to us. Finally Dad came out. As Dad, Casey and I left, I looked back and saw the man spraying his hands with Lysol.”

But I like to do what scares me. Also, my acupuncturist, Liz Greenhill, told me to write down five things I like about the book. So I did. I come from a cynical, nihilistic music scene full of brilliant, sardonic people. I know that some of my writing will seem too sentimental to them. Other people will hate the fragments. Paraphrasing my friend Danielle Vermette, it comes down to: either your imagination likes their imagination, or it doesn’t.

TD: You went back for your MFA, later in life (age 42). Were you better prepared? What are your thoughts on the way we’re still running workshops in graduate programs?

AB: My son was three at the time, and it was hard. I took writing classes for the first time, such as fiction workshops, essay writing, immersion reporting, magazine writing. I had taken lit classes at UC-Berkeley, but at the grad level at PSU it was more intense with documentation and justification. I got a 4.0, but I also took on a horrendous amount of student debt. I lost my source of income in 2008 when the educational publishing industry partially collapsed, and my husband wasn’t working. Now I do income-based repayment, but I will owe Nelnet until I die. I do not recommend grad school unless you can work through it. I also had a naïve view of adjunct teaching. I thought it would pay at the same rate as writing ed pub stuff, but the hourly rate is for classroom only. I also had a naïve idea that I would get a book out right away. (See: that is a lot of self-criticism!)

Generalization: online fiction classes are not conducive to improving writing. I took one and had little engagement with other students. You can’t take in text solely from the screen. You need to hear the person read it and know the person. The in-person workshop paradigm follows a model of a “good story” that is scene-based and involves a Calvinistic work ethic. We ask it: What is not working? Was the ending “earned”? Is this “received language”? The character doesn’t change in the end—so is it a failed story? Is the dialogue “flat”? Does it drive the story forward? It’s literature as Manifest Destiny. What is conquered at the end? The best antidote is to read stuff from authors who are not white male Americans (although I did love reading The Scarlet Letter to prepare for my thesis defense). That said, I love taking classes. I’ve taken memoir classes, poetry classes, and flash fiction classes since graduation, and I’ve taught teens through Writers in the Schools. I am the Model of a Hypocritical Woman.

TD: Time and place in this book are so present. From “White Pants” with the Loves Baby Soft to the San Francisco punk scene, you’ve really captured the west coast in a distinct time period. Did you set out to do that? Is place important to you?

AB: I do check stuff. I had a character knocked out on Ambien, but it wasn’t on the market yet. Yes, place is important. I am a sensitive little puppy, so it’s easy for me to take in environmental details.

TD: A recurring theme seemed to be disillusionment and disappointment with love—even if appears normal on the surface. In in the “The Garden,” the main character says about her husband, Phil (with whom she’s been relatively happy) that “I had been with him so long I rarely saw him clearly. In, “The Courtship of Eddie’s Father,” the character thinks he’s fallen for the birth mother of his child. In “Sentient Times” there is the great line, “All marriage vows are lies.” Is this a theme that unites these pieces?

AB: Trust, reconciling the past, fitting into a family when you might feel like an outsider, loss, loneliness. The earliest books I loved had those as themes: The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter, as one example. Jane Eyre. Corduroy.

TD: You pushed form a lot in this book, borrowing from your journals and notebooks for some of the more experimental pieces. Even in a more straightforward narrative, like “My Martian Launderette” where people can’t touch each other, you’re still tackling existential loneliness through a more sci-fi narrative. It is just such a wide body of work—in terms of form. Did you have fun with this?

AB: Yeah, I had fun because I have “in jokes.” For instance, “Teenage Riot” comes from a Sonic Youth song that I loved when I felt like a “tuff gnarl” or dated people like that, but to put that on a bunch of diary entries by a nerd made me laugh. I used to work on a fanzine called Bananafish, which included found letters, interviews with extreme noise artists, and surreal (using that term because the founder does love Dali) record reviews. That set the bar for a collection. Since I’m a musician, I wanted an album-length feel into the book (not “filler” but variety), and I wanted a hybrid energy. I also didn’t have the psychological strength to write longer stories. Two of the newer ones are from a novel I’d started. I dropped out of a novel writing class because one man in it was abusive to me and my writing, when it was a draft, and I almost took the story out of the book. I didn’t want it to “smother” anyone (coincidentally, a lot of the language he used echoed the complaints of my ex-husband). I was suffering. Who was I if not a wife? I was also a psychological mess, so it would’ve been hard to create a long story with a character who goes up the traditional mountain to have an epiphany, climax, and cigarette (or vape).

TD: What is your process? You copy edit for a living and you have a son and still you’ve just published a collection of 28 stories. How do you balance your life and find time to write?

AB: The best thing I can do is take classes, since I’m a distracted person. It’s hard for me to allow myself to write (due to self-judgment). But a class has that veneer of obligation. Copyediting is grueling and hurts my wrists. I have a son who I’ve had full responsibility for since November 21, 2016, and no family around. I think that’s why I have to gloss over people’s photos and news of writing residencies (I’m especially envious of being around trees). I play classical piano, make quilts and eye pillows, post too many photos on Instagram, and I still want to get in a full-time band again (I play bass).

Alex at the Powell’s launch on Oct. 12, 2017. Photo by Laura Stanfill

TD: You’ve been compared to everyone from Miranda July to John Cheever. (I’d thrown in Quentin Tarantino for my favorite of the collection, the cinematic story, “The Scorpion.”) Who are your influences?

AB: Thanks, I hadn’t thought of Tarantino. I’ll tell you the books I’m reading or have read recently (I also love Paris Review): The Book of Joan by Lidia Yuknavitch, Child Finder by Rene Denfeld, I Am Not Your Negro (the dialogue of the movie, set as poetry), chapbooks for my poetry class, Field Theories by Samiya Bashir, Sing, Unburied, Sing by Jesmyn Ward, The Glamshack (also on 7.13 Books) by Paul Cohen, You Don’t Have to Say You Love Me by Sherman Alexie, Shot in the Heart by Mikal Gilmore, Darkansas by Jarret Middleton, The Dreamlife of Debris by Lance Olsen (I interviewed Lance for the online journal Propeller), and Narrow River, Wide Sky by Jenny Forrester (I interviewed Jenny for Propeller, too).

I’m not sure that answers your question, though. I worship many writers, artists, and musicians. I will blow money on $$ concerts (front row at Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds). I forgot to breathe while watching Nan Goldin’s slideshow The Ballad of Sexual Dependency last summer (with music) in NYC.

I named the book Planet Grim from a line in an email to my friend who had published Bananafish, about the state of my marriage. But it also echoes Grimm’s Tales. They are an influence. I read a lot of fairy tales and myths as a child and in college (folklore classes as an undergrad).

My dad used to tell me stories about the Three Pigs, except Mortimer was a detective (a good way to retell Sherlock Holmes stories). One time he made Mortimer into a reporter who had to investigate the tunnels built by the Viet Cong, and he told me on walks at night in the Connecticut woods about tiger pits lined with poisonous bamboo spikes. My dad was a reporter on the front lines (he went there three times). He’s one of the most optimistic people on the planet, but he recognizes the value of darkness. And my mom says, “You can’t go wrong with nice,” but she has a sly sense of humor. I always have my notebook out around to write their quotes.

TD: Typical day for you? Do you try to read a lot? Do you have a favorite place to write?

AB: I like to write on my couch in notebooks. (yes to reading) I’m about to do a writing residency at a Portland high school. I’m looking for a full-time job because I have fears about medical premiums next year. I read a lot of political articles, especially at 2 AM. Reading about the Russia investigation is soothing.

TD: What’s next? Poetry? More shorts? A novel?

AB: I’ve written a memoir, pieces of which have appeared online and in print. Not sure what to do with it (anything?). My friend says I should do something with my diary excerpts, but I know from Mortified that my story is not unique. They are funny (to me): age 14: “I got tired of the disco beat after six hours. Slow dances were fun except when guys were all hands. Especially if they’re not cute. … No one knew I was smart.”

I’m excited about my poetry class with Matthew Dickman, which goes until December. We’re going to print a chapbook at the end of it.

COMMENTS ARE OFF THIS POST