It was near the end of the year and Sunil could recall very little of note for the region except for West Indies winning the Champions Trophy. It wasn’t that he didn’t take note of current events, as was the case for his father who could barely be bothered what year they were in. In fact, Sunil read the newspaper every day from front to back.

There was little else to do in his job as a watchman. He didn’t even need to watch the agricultural equipment he was hired to guard. The tractors and harvesters had no resale value. The company had been trying for years to sell them off, first as they were intended and later for parts. No one took any interest. He spent most of the night asleep in the cabin of a dump truck and only woke at 4 a.m. to collect the daily delivery of the newspapers for the estate. Since he wasn’t allotted one until the start of his night shift, he always had to resist doing the crossword in the morning before placing the newspaper back into the box.

Nothing ever changed much in that area. The most momentous occasion had come a few years before when the sugar factory had closed down and its vast tracts of land were redistributed to compensate for the loss of jobs. Even that had progressed smoothly with barely a protest or raised voice. The government knew how to stop any unrest. Give the workers land and they’d immediately stop any trouble themselves. Land was what most of them were working for in order to buy. Sunil had heard of the importance of owning land his entire life from his father and grandparents. Every other person of Indian descent he knew had grown up hearing the same thing. It wasn’t a new idea either. Saving money to own land or migrate was the plan for everyone.

There was no television in the house Sunil lived in. If he needed to watch cricket he would go to the rum shop in the industrial estate. There was nothing else he felt he needed to watch. Having never owned a television, he didn’t care about any of the popular serials. Even the cinema barely interested him. His father and sister loved going to watch Bollywood movies but he never found them appealing. Fantasy wasn’t something he cared about. There was too much that was real and interesting to waste time thinking about fiction.

The rum shop on the estate opened irregular hours compared to the ones in the villages and even in the city. Catering to workers who worked irregular hours, it carried the regular signboard stating the owner was licensed to sell spirits at any time but was the only one that actually followed it. The owners lived above the rum shop which also served as a restaurant. Sunil often had breakfast there and would sometimes remain for the entire day if there was a particularly exciting day of cricket.

After breakfast, the rum shop was never crowded. Most workers on the estate would drop in for a beer or two but rarely would any stay for a long. It was difficult to be social in the same complex where they worked. The period after the clearing of the breakfast crowd but before people started showing up for lunch was Sunil’s favourite time. It was quiet enough to hear the commentary on the television yet was still possible to listen to any interesting conversations from the few people who remained. He rarely joined into any conversations but he always felt that he probably had one of the best understandings of what was happening in the estate and by extension, the country when the scope of the conversation expanded as people drank more. It was this more than any other reason he stayed so often. He rarely drank.

Barely anyone was on the estate then. Most workers across the country spent the time between Christmas and New Year avoiding work and using the holidays to visit family abroad or just spend time with their own families. Only those who had no strong ties spent the holidays working regular hours. The country was neither particularly religious nor particularly Christian but the festivals were celebrated across religious and ethnic lines. No one wanted to miss an excuse to have a party.

Sunil didn’t care about Christmas. There was no celebration to look forward to. His father and sister had gone to see his grandparents in the south. He had told them it wasn’t possible to miss work but he could have easily gotten the time off if he wanted to. But he always felt uncomfortable with his extended family. Though they lived on the other end of the expanses of sugar estates in a rural existence perhaps even more traditional than his, he often felt they had little in common. Even if he changed his mind now, there was no way to get there. Public transport didn’t go that far into the countryside and his uncles who worked in the north and central had already gone down to the house.

Other than Sunil, a group of older men were the only ones in the rum shop.

The old men were talking loudly. They were perhaps approaching their mid-fifties at oldest but their faces were lined and cracked. They were likely former sugar cane harvesters. It was hard to estimate their ages. Most had begun to work when they were in their early teens. Years spent in the heat of the tropical sun, among the charred stalks of the sugar cane caused their faces to age quickly. It was the least of their worries. Spending all the time near the smoke of plantation fires meant many would get lung problems, which would then make it impossible to continue manual labour.

They were talking about the state of the country. It was a topic that was being discussed among numerous households across the country. Sunil knew he wouldn’t learn very much by listening but he listened anyway. Most conversations about the country or the budget happened only so that people could complain. Rarely would anyone offer advice or an alternative idea. And even if they did, what would that accomplish? The only constant was that the fault lay with the current government. During the years when the Indian dominated party had been in power, the constant argument (at least in the estate) was that things weren’t as bad as the newspapers were saying. The newspaper had conveniently started to be accurate when the current government took office, of course.

“Tell we something, too. You must have something to say,” one of the men said.

It took Sunil a moment to realize he was being spoken to.

“But I don’t have nothing to say. If I feel I could add a little something, I go say what I have to say,” Sunil said.

“Alright, well come and sit we with nah. Don’t be one-side so in the season.”

Sunil moved over to sit with the men. He was given a beer that he didn’t ask for. They shifted to give him a spot where he could still see the cricket. England was batting safely and trying to see out the end of the day’s play. It was the type of cricket that made people yearn for the shorter format of the game. Especially in the Caribbean.

The man who called him over continued talking. He had glasses that reminded Sunil of Clive Lloyd when he was the captain of the West Indies.

“So, how you here alone around Christmas season?” the man with glasses said.

“I working tonight. Have to keep an eye on the place.”

The men began talking among themselves again.

“Man, things falling apart here. Nothing to keep a eye on. Everyday somebody going away to live. Long time now people going little bit but never so much so,” a man on the other side of the table said.

“And is a different kind leaving. Back in the day is only men who had good education or no education at all went America to stay. Now is normal people with normal job,” another man said.

“Before, men with no education went and hide and stay,” the man with glasses said. “Them didn’t have no problem living like criminal. But now men who have no reason to live like criminal going America to hide and live.”

“The way thing going now you can’t blame them.”

It was the man at the far end of the table who spoke. Sunil couldn’t see him that well as he was partially in the shadows. He could see a gold tooth shine when the man opened his mouth. From the way everyone else stopped talking it was clear that he was going to continue and also that the rest of the men valued what he said.

“This country wasn’t always so bad. Even when we had recession and nobody could have find work, all of we didn’t go and rob and thief. Up north them always had they bad-john behavior and plenty trouble used to happen but it was always little thing. Any time I watch news and I see Jamaica and Guyana I does say is a good thing we is how we is because we could have be like them. But the way thing going them go say just now is a good thing them not like we.”

“Even when it had problems they never spread all over,” the man with glasses said. “People who vex was vex with other people and had reason. They wasn’t just going all over to cause problem for everybody. This kidnapping thing that going on not right at all. People thieving people. How you go do that?”

“How a man go thief a next man child and take money to give the child back? Men does rob when things bad but them men does be stupid. But you can’t plan no kidnapping and not get catch when you stupid. People who doing kidnapping could probably do all kind of thing with the brain them have but they doing wrong thing.”

Sunil had heard about the kidnapping spree over the last two years. It was highly sensationalized in the newspaper. But he thought of it as a problem that affected only the rich. He had no fear of being kidnapped and he doubted anyone he knew worried that their children would be. Kidnapping was something that poor people up north did to rich people of the north.

“You ever feel like the police might know who it is doing all them kidnapping but they don’t care to do nothing because they taking bribe?” Sunil asked.

Saying that brought about a huge flurry of dissent from the men.

“No man. How you go say that? Police there to do the right thing, “the man with the gold tooth said. Even if one or two of them know things and don’t say nothing, the rest must find out. Bribe is a serious thing. I mean everybody does take a little bribe and thing, especially when Christmas coming up and they need a little spending money. But never for nothing serious like that. If police start to do that then all of we really better go.”

He leaned forward as he said this and Sunil saw his face clearly for the first time. He was as old as the others but had jet black hair that Sunil felt sure was dyed. There was a patch of pink skin at the end of both of his eyebrows. They were the first signs of vitiligo.

The old men lacked the cynicism that Sunil had. Sunil himself hadn’t even realized when he had begun to be skeptical about the integrity of any of the country’s institutions but he knew by now he didn’t have much faith that people in charge could be relied upon.

“It could happen though. If everybody realize things getting bad, they go only be looking to do thing for themself,” Sunil said. “I know some of the people who gone in police. It might have be different before but now I can’t really say them fellas go do thing for people just because is that they supposed to be doing.”

“Well, I can’t say for sure about the young fellas and them. But I would have hope that the old policeman and them would know better than to put them kind of men in the force,” the man with glasses said.

“Is only them kind want to be police,” Sunil answered.

The cricket had ended. Sunil also got the feeling that he had driven the conversation to a dead end. The men certainly didn’t seem eager to talk anymore.

“Alright, well don’t work too hard. I sure I don’t have to tell you that,” the man with glasses said.

The rest were silent as they got up from the table. Most didn’t even look at him. He couldn’t tell why they were acting as though he had embarrassed them when none were policemen. Perhaps they felt as he did but had never spoken those feelings aloud.

Sunil left shortly after the men did. With the day’s play over there was no reason to remain at the rum shop. He couldn’t stop feeling uncomfortable with himself even though he knew he had not said anything wrong.

______________

Sunil was late getting to work. He always slept deeply after drinking beer. Even one beer would make him sleep well. One of the reasons he didn’t drink often was that he was afraid of always needing to drink to be able to fall asleep.

It didn’t matter if he was late. He signed in the time he arrived himself and there was no one else to corroborate this. The important thing was that he was there in the morning when the security guard for the day turned up to change with him and receive the perpetual report stating the night was quiet. Even though being late didn’t matter Sunil always tried to be on time. It was a good habit to be on time.

The estate was quiet and even darker than usual. The mechanic’s shed where there were also people on call during the distillation high season was empty now that the season was over. Sunil doubted there would ever again be mechanics on call. There would not be many future harvests, if any. The only light came from inside his hut and the darkness made it easier to see the flares from the oilfields in the night.

Because he had slept before coming to work, Sunil was unable to sleep as he usually did. The radio in the guard’s hut didn’t work very well. No matter how many adjustments were made to the dial, the stations were never fully clear and there were always disruptions from static. It was a new problem. The radio had only been like this for a few weeks but there was no date yet on when a replacement would arrive. It usually made no difference to Sunil but he would have welcomed a bit of parang since he was awake. He kept the radio on anyway.

There were no books in the hut other than a bible and a dictionary. They both belonged to the day guard. Sunil was fairly certain they were never read. The bookmark had been on 1 Peter 2:11 for months now. It was possible that the bookmark stayed there as a reminder to abstain from excess. But that reminder was surely a waste in the hut, Sunil thought.

He remained lost in thought for a while, mostly about the conversation earlier in the day and whether the men were right or he was. If the police and the criminals were separate groups working against each other, then there was hope for the country. If it was as he believed and they were all working together, then things were probably going to get worse. It was easy to think about these things abstractly. He still felt as though living in a rural area would insulate his life from any major worries of crime.

Around midnight Sunil got up to take a walk. There was usually no need to walk about but he felt that he needed to stretch his legs. It was only once he left the hut that he heard noises coming from inside the yard.

As he walked towards the old garage the noise became louder. It didn’t sound like anything distinct, only a dull metallic pounding. His first thought was that someone had left a machine on but he immediately dismissed the idea. No machine had been turned on since August.

Sunil thought about how inadequately prepared he was for dealing with any intruder. His job was to watch. His presence was supposed to scare off any potential bandits. He was not supposed to actually do anything. It would be better to call the police, he thought. But it was the holiday season and by the time the police came any bandits would be gone. If the place got robbed while he sat and waited on the police, then he would surely be castigated for doing nothing. If the police came and there was no robbery in place or worse, if there had been no robbery at all and he was mistaken then he would probably be in trouble for wasting police time. It was better to see what was happening before calling the police. But just because it was the better thing to do didn’t mean it wasn’t a bad idea.

The light in the old garage hadn’t been turned on but he could see that there was a light on inside. The light flickered and when he got to the door he could see that the light came from a flambeau.

There were two men at the tractor parked next to the door. They seemed to be pounding at the wheel of the tractor. The noise was far louder at the entrance of the shed. Sunil was surprised that it wasn’t more audible from the security booth.

Now that he was sure there was a robbery, he decided to call the police. If they came too late it was still the best thing to do. The owners of the estate couldn’t expect him to confront armed men. Hammers could do a lot of damage and Sunil had been given no training for his job. Sitting and waiting was the extent of his job description.

He turned to go back to the guard booth and call the police. He found himself in the path of a third man.

“Alright boss, who you is and what you doing here?” the man asked.

Sunil realized this was the question he should have asked if he was brave enough to confront the men. He was too scared to laugh at the reversal of roles. He didn’t say anything.

“You dumb or what? If you dumb you can’t say nothing so you can’t tell nobody we here but if you only playing dumb I go get real vex here,” the man said.

“I not dumb,” Sunil said.

“Walk inside there. Fast.”

Sunil looked down and confirmed that the man was also holding a hammer. It would probably have been possible to run away. There was enough room to run around the man. But he couldn’t be sure that he wouldn’t be caught. He had never been the fastest runner. And he was afraid of being caught and punished for trying to run away. He walked into the garage.

“Who this man is you bring in here?” the man at the front wheel asked. His voice wasn’t clear and Sunil couldn’t see his face clearly. As his eyes adjusted to the semi-darkness inside he then saw that the man had a black bandanna around the lower half of his face covering his nose and mouth.

“Me eh know. I find him outside standing up by the door. He don’t want tell we who he is but me eh feel he and all come here tonight to do the same thing like we,” the man who had caught him said.

“Is the watchman,” the man at the rear wheel said. Sunil couldn’t see him anymore from where he was standing.

“How you know that?”

“Who else it go be?” the man at the rear wheel said. “Go by the watchman booth and check if is he. If is not he then is better we sure the watchman still in the booth. But if this fella is not the watchman then we don’t have nothing to worry about. That watchman letting everybody come in.”

Sunil felt a slight surge of anger at the insinuation that he would allow the place he guarded to be robbed with his consent. But he didn’t say anything.

The man from the rear wheel came around to where Sunil was. He also had a bandana around his lower face but despite this Sunil recognized him. He had the same glasses as in the morning.

“Wait nah, is allyuh robbing this place?” Sunil said.

“Who allyuh? Who you feel we is?” the man with the glasses said.

Sunil wasn’t sure if they hadn’t recognized him or they were just pretending not to. He briefly thought that he was being given a chance to pretend he didn’t know them and they didn’t know him. It was probably dangerous to tell thieves that they were known. But he hadn’t felt that these men were criminals. They were just men.

“Is me from this morning. In the rum shop.” Sunil said.

The man who had went to check the guard booth came back.

“Nah, it don’t have nobody in there.”

“Look your boy from this morning come to check we here. I couldn’t make him out in the dark before,” the man with the glasses said.

“Wait nah, you is the watchman here?” the man who had gone to check the guard booth said. Sunil saw up close that it was the man with the vitiligo. Unlike the morning where he had seemed in charge, now it was clearly the man with glasses who was giving the orders.

“Yeah, I is the watchman here. But what allyuh doing here. Just this morning is all kind of talk about crime bad and the country getting too bad and then is allyuh same men is the criminal?” Sunil said.

“Not all of we could go abroad. Things really getting out of hand. Is best we get the most we could get now,” the man with glasses said. “Just now all you need to go America is to tell them you from here. They go keep you one time and tell you they can’t send you back. I hear they done doing that when Jamaicans go.”

“Nah man. You can’t say things getting bad so you go do thing to make it worse. That not right at all,” Sunil said.

“It coming. You could only lie to yourself for so long. We can’t stop nothing from getting bad here. Once that estate close the only thing we could have get is land to farm. This age I is now is no kind of time to learn to be a farmer.”

“But is years of work allyuh have. You must get something somewhere.”

“That don’t matter. Is the same place we was working you working. But is not talk we come here to talk,” the man with glasses said.

“But I can’t just let you go with all the thing in here. I mean I is watchman. Is me to stop the place from getting rob,” Sunil said.

“You going and stop all of we? You alone?” the man with vitiligo said.

“Rest a hand on him and let we done all this talk nah. The more time we waste the more likely somebody go come,” the third man said. He hadn’t spoken before and had continued working on the tractor.

“Hush you mouth,” the man with glasses said to him.

He addressed Sunil next.

“But hear nah, he right you know. We don’t want no set of trouble here but you can’t do all of we nothing.”

“So what I go do when they come and see the place rob?”

“He worrying about he job when all of we loss all we own,” the man with vitiligo said.

“Nah, he right to worry. He see what does happen when you loss your work and have to be like we,” the man with glasses said.

“Tie him up. They go can’t say nothing then,” the man who continued working said.

“Look, hush you mouth nah,” the man with vitiligo said. “You talking a set of stupidness.”

“Nah man, don’t hush him. Is the first piece of sense he talk probably in he life,” the man with glasses said.

“Wait nah. What you saying? You go tie me up and leave me?” Sunil said.

“Listen, if we tie you up then the boss go can’t say nothing. The thief and them find you and tie you up,” the man with glasses said. “Then they rob the place. None of that is lie. You keep your work, we don’t have to rough you up. Everything good.”

“But I go have to stay here tie up till morning.”

“When we leaving we go call police and say we hear noise. That good enough for you?”

Sunil wondered if this meant that they were already working with the police and the police knew about the robbery. His cynicism that morning about police and criminals possibly working together had seemed to disturb the men.

“The police go reach here tomorrow morning. You know the speed policeman does work and worse yet holiday season,” Sunil said.

“They go come fast. Don’t worry,” the man with vitiligo said.

Sunil took that to be confirmation that the men had close contact with the police. No one without friends on the police force could count on the police being prompt. It was the same for ambulances. The most frequent response when calling either service was that there was a lack of vehicles to send anyone out to respond.

“You want me help you so we could finish faster?” Sunil asked. He had resigned himself to the men’s idea being inevitable.

“What you know about fixing tractor? Just hold on right there till we ready for you. Next thing they find your fingerprint over everything, how it go look?” the man with glasses said. Sunil hadn’t noticed before but they were all wearing gloves.

________________

They tied him up after they finished removing tyres and machine parts. Only his hands were bound and they used the plastic fixing strips from inside the garage itself. He tested if he could free himself but he wasn’t able to. The men had made it seem believable.

They had said they would call the police immediately and he had seen the man with vitiligo pull out his cell phone and make a call but he hadn’t heard the contents of the call.

Sunil thought about what his story would be when he was found. He thought it was best to say things as close to the truth as possible. That he had heard a noise and gone to check what was happening and had been caught.

He wondered if he would ever see the men again. He thought it was likely that he would. Most former workers stayed around the estate. If they were there during the holidays then they definitely had to live nearby. But then again maybe they were just there in preparation for the robbery later, he thought.

It was possible they were trying to get enough money to buy a ticket to go abroad. He didn’t know how much they would get for what they had stolen. He hoped it would be enough for a ticket and that they were going abroad. Because he hoped to never see them again. If he ever saw them again he didn’t know what he would say.

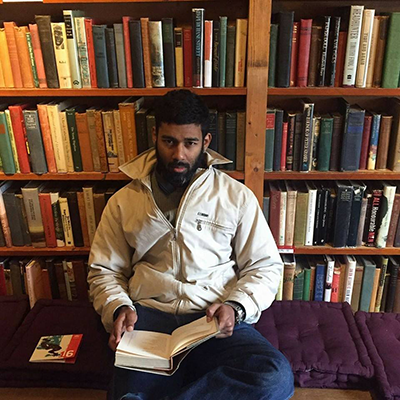

Shastri Sookdeo was born in Toronto but grew up in Trinidad and Tobago. He nows lives in France where he is pursuing a Masters in Supply Chain Management. His non-fiction writing has appeared in The Write Launch and Your Commonwealth.

5 Questions with Shastri Sookdeo

TD: Tell us a little about this story? Where did the idea come from?

SS: This story has its background in the closing on the sugar cane factories in Trinidad in 2002, which was a major event for many communities. Much later, in 2010, I started spending time in some of the former sugar producing areas and I regularly heard stories about how the loss of jobs led people to migration or criminality. I was then able to develop this story, basing it on an extension of those stories I’d heard.

TD: Who is your greatest writing influence?

SS: Albert Camus. But I’m also influenced a lot by the indirect way many people tell stories in Trinidad, where the stories have detours and are rarely straight to the point.

TD: What is your favorite place to write and why?

SS: I’ve moved recently but before that I spent a lot of time writing at my local pub in the morning before it got too crowded and noisy, mostly because they had free coffee refills and more comfortable chairs than at home. Now, most of my writing gets done at my desk in my apartment, because it’s familiar and convenient.

TD: Favorite word?

SS: Verisimilitude. I never get to use it but I think it’s best for describing how stories should be. If you look at my writing, I think I overuse the words “in fact”.

TD: Do you have a favorite reading ritual?

SS: I usually read while I’m eating breakfast or lunch as well as on the train.

COMMENTS ARE OFF THIS POST